The Columbia Phonograph Companies

As the popularity of the coin-in-slot phonograph rose in the 1880s and 1890s, requests began to form from showmen for records of songs and instrumental music. This demand gave birth to the first “modern” record company, the Columbia Phonograph Company, who produced wax cylinders. [1]

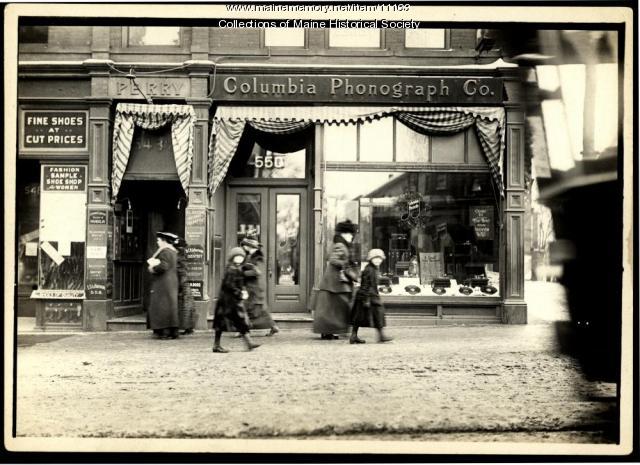

The Columbia Phonograph Co. at 550 Congress Street at the corner of Congress and Oak streets in Portland, 1912.

“Columbia Phonograph Co., Portland, ca. 1912” Maine Memory Network. Accessed October 29, 2019. https://www.mainememory.net/artifact/11163

The Copyright Act of 1909

Because other music-playing and visual devices, including the player piano, but also the nickelodeon and movie theaters, were more centered in public focus than the phonograph, regulations at the time acted in favor of the soon-to-be jukebox.

Copyright law in the United States had not been modified since 1790. At this point, President Theodore Roosevelt would argue that “[United States] copyright laws urgently [needed] revision,” as current laws carried no provisions regarded the reproduction of materials. [2]

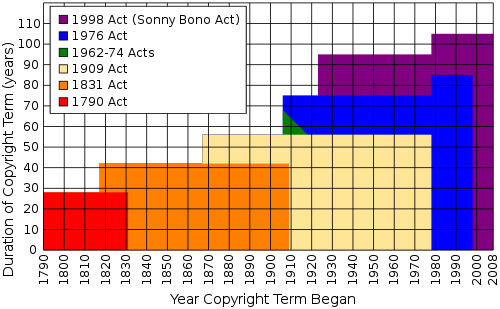

This graph , created by Tom Bell, shows the expansion of U.S. copyright law over the years. The Copyright Act of 1909 is listed in yellow.

Tom Bell. “Expansion of U.S. copyright term (assuming authors create their works at age 35 and live for seventy years)” Wiki Commons. November 27, 2008. Accessed October 29, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyright_law_of_the_United_States#/media/File:Tom_Bell’s_graph_showing_extension_of_U.S._copyright_term_over_time.svg

It was a this point that the jukebox would gain another key advantage in the selection/rejection process due to their cheapness to operate and profitability. [3]

Record Sales in the First Decades of the 19th-Century

However, with the introduction of Prohibition in 1920, many saloons, bars, and other spaces for entertainment had to severely reduce their operations or close their doors entirely. This, coupled with the advent and rise in popularity of the radio, made many question the direction of “coin-operated phonographs,” player pianos, and other music-playing devices. [4]

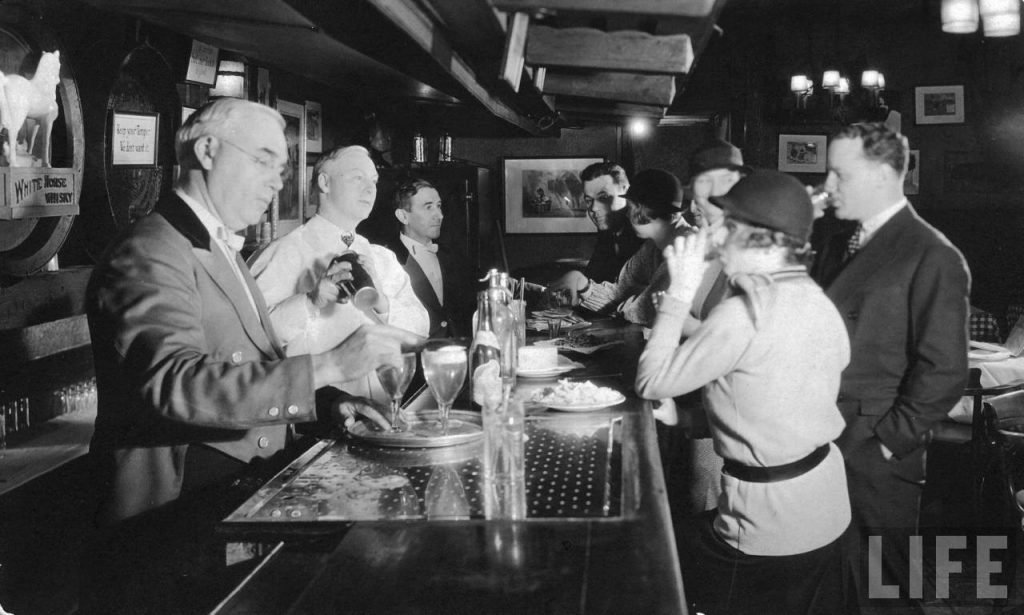

A 1920s speakeasy known as the “Hunt Club.” Here, it was common to listen to ragtime and swing music.

Margaret Bourke-White – “Prohibition Photos Inside the Speakeasies of New York in 1933.” The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images. Accessed October 29, 2019.

https://time.com/3613626/prohibition-photos-inside-the-speakeasies-of-new-york-in-1933/

Records versus the Radio in the Prohibition and Depression Eras

In the competition between radio and the record, the Great Depression seemed to give radio and advantage, as radio was able to still be funded by advertising, whereas records were not.

The radio and the phonograph enjoyed a strangely symbiotic relationship. As more Americans listened to the radio, they became accustomed to enjoying a wide variety of music. Further, developments made to the radio allowed for audio technology to increase across all industries, an improvement that would also be utilized by the phonograph. [5]

During the Great Depression, record sales took a toll, and the fate of the phonograph appeared to be uncertain. Thankfully however, many major record companies were bought out by already successful radio networks, such as Colombia Broadcasting System (CBS), allowing them to flourish. [6]

The Record Album and Billboard

During the Great Depression, the radio proved to be a formidable piece of competition for the jukebox, as it too “ceased to be a novelty.” As stated previously, the buy-out of many record producers by the radio network actually helped promote the music industry, and therefore, the jukebox. [7]

In the 1930s, one of the most popular genres of music was swing. A notable producer of swing records was Decca Records, who, at the time, were the unit volume sales leader in the industry. Interestingly, this was the same year that saw the introduction of modern record albums, and by 1937, Billboard would begin its “Week’s Best Record” category. [8]

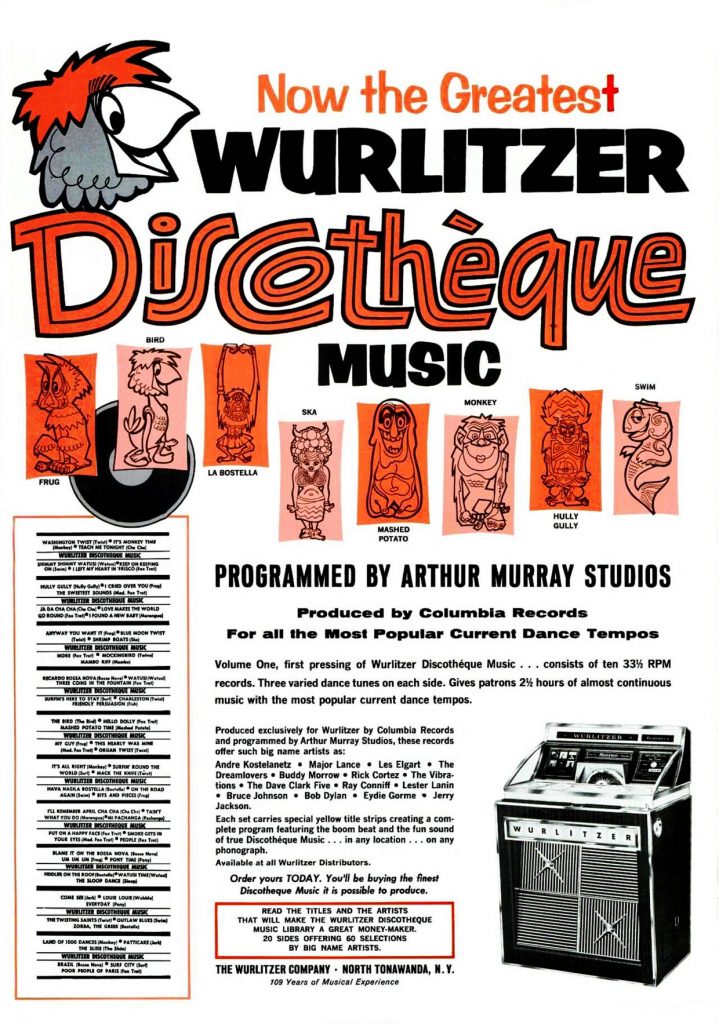

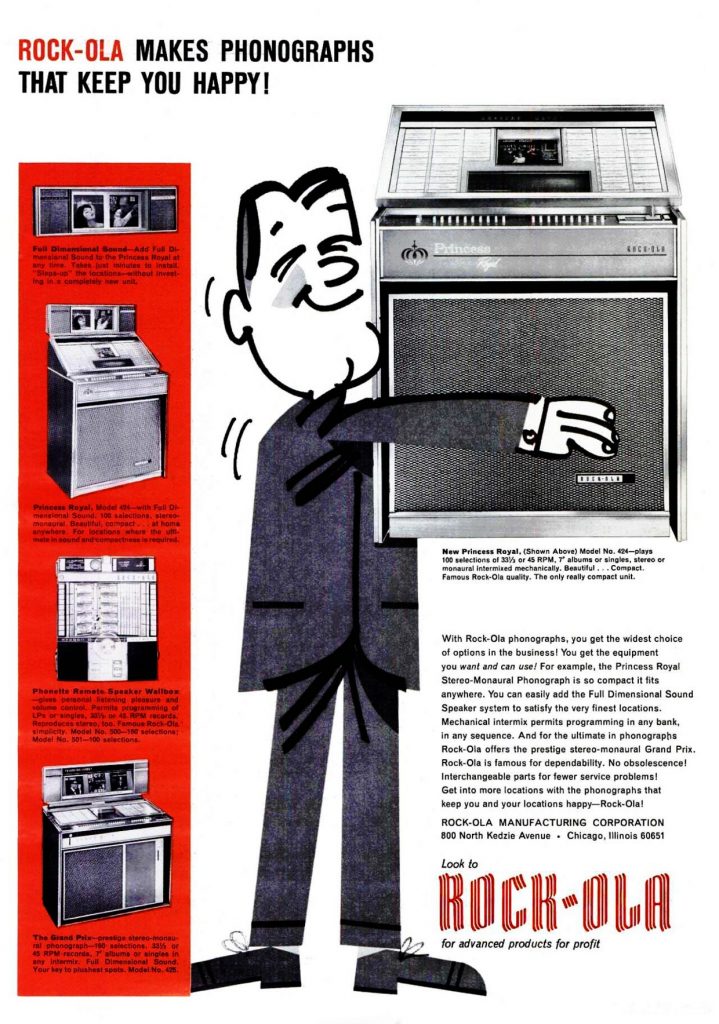

Billboard played an important role in the growth of the jukebox, as jukebox companies took out many advertisements in their magazines. Jukebox advertising in Billboard would be prominent well into the 1960s, as seen below. Note that the ad for the Rock-Ola jukebox still refers to the machine as a “phonograph.” [9]

Wurlitzer Jukebox Advertisement in Billboard Magazine, 1965.

“Now the Greatest Wurlitzer Discoteque Music.” (Motor City Radio Flashbacks, May 15, 1965.) Accessed October 30, 2019. https://www.mcrfb.com/?cat=609

Rock-Ola Jukebox Advertisement in Billboard Magazine, 1965.

“Rock-Ola Makes Phonographs That Keep You Happy!” (Motor City Radio Flashbacks, May 15, 1965.) Accessed October 30, 2019.

https://www.mcrfb.com/?cat=609

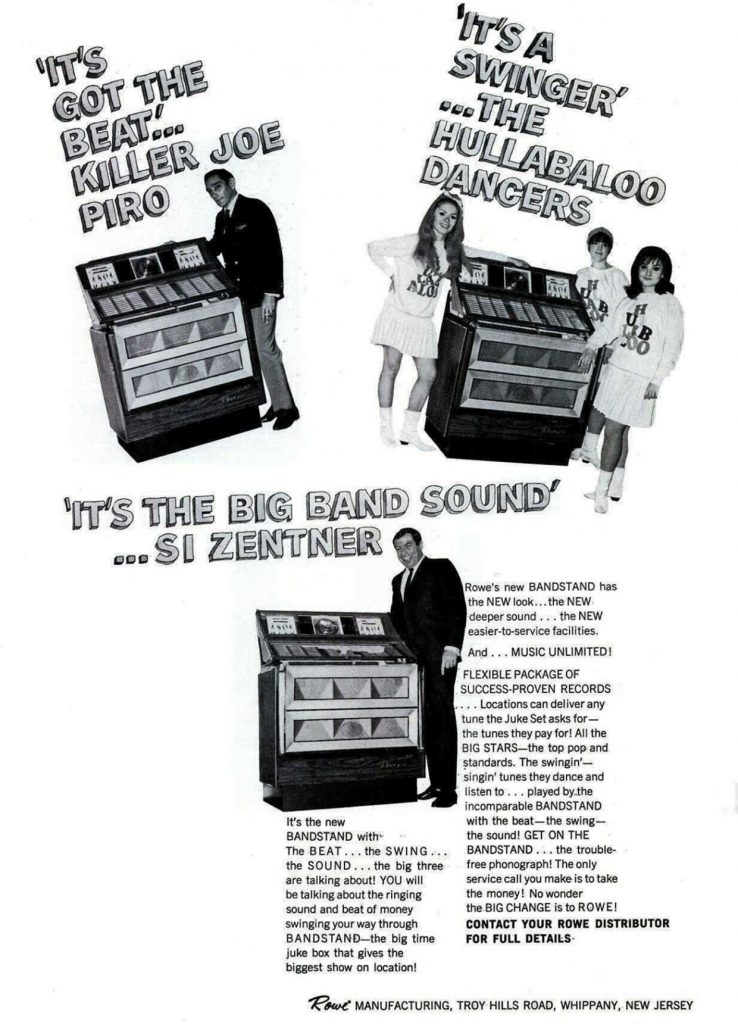

Rowe Jukebox Advertisement in Billboard Magazine, 1966.

“It’s Got the Beat…” (Motor City Radio Flashbacks, January 29, 1966.) Accessed October 30, 2019. https://www.mcrfb.com/?cat=609

Wurlitzer Jukebox Advertisement in Billboard Magazine, 1966.

“Turns Any Spot into Funsville.” (Motor City Radio Flashbacks, February 05, 1966.) Accessed October 30, 2019. https://www.mcrfb.com/?cat=609

Key Takeaways

Tumultuous and Uncertain Times

The early modern record industries, like the jukebox and music industries as a whole, existed in a rocky, gray space for the earliest decades of their existence. Through the tumultuous periods of Prohibition, the Great Depression, and World War Two, it was unclear whether or not the newly-formed record insures, which were necessary for the existence of the jukebox, would take off.

Without the early merge between radio and record companies, it is possible that the industry as we knew it in the mid 20th-century would not have flourished in the way that it did.

The Importance of Advertising

Advertising through publications such as Billboard was crucial in promoting musical artists and jukeboxes alike, as advertisements grew public awareness and helped create a culture of individual music participation.

Desire for Music Genres

Finally, the record industry, and, by default, jukeboxes, were able to grow because of public desire for modern music in the genres of ragtime, swing, jazz, and eventually, rock & roll. Importantly, record companies offered platforms for artists to spread their music – eventually in the form of long-playing (LP) albums. The increasingly fast-paced nature of the music industry worked hand-in-hand with the spread of phonographs and eventually jukeboxes, as individuals had the ability to choose exactly what new music they wished to listen to – something that the radio could not offer them.

Notes

1. Katie Kitamura, A Separation (New York: Riverhead Books,2017), 25.

[1] Kerry Segrave, Jukeboxes: An American Social History (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2002), 7.

[2] “The House Report 1 on the Copyright Act of 1909” (February, 1909), 1. https://web.archive.org/web/20111020035955/http://ipmall.info/hosted_resources/lipa/copyrights/The%20House%20Report%201%20on%20the%20Copyright%20Act%20of%201909.pdf

[3] Segrave. 39.

[4] Ibid. 49.

[5] Ibid. 42.

[6] Ibid. 49.

[7] A Voice, “History of the Record Industry” (Medium, June 07, 2014) Accessed October 29, 2019. https://medium.com/@Vinylmint/history-of-the-record-industry-1877-1920s-48deacb4c4c3

[8] Steven Long, Derek Jacques, Paula Kepos, Stephen V. Beitel, and Ed Dinger, eds, Nielsen Business Media, Inc. International Directory of Company Histories (St. James Press, September 11, 2013), 260-265.

[8] Ibid.